BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA TROMBONE SECTION INTERVIEW

International Trombone Association Journal July 2008/ Volume 36, Number 3, Page 21

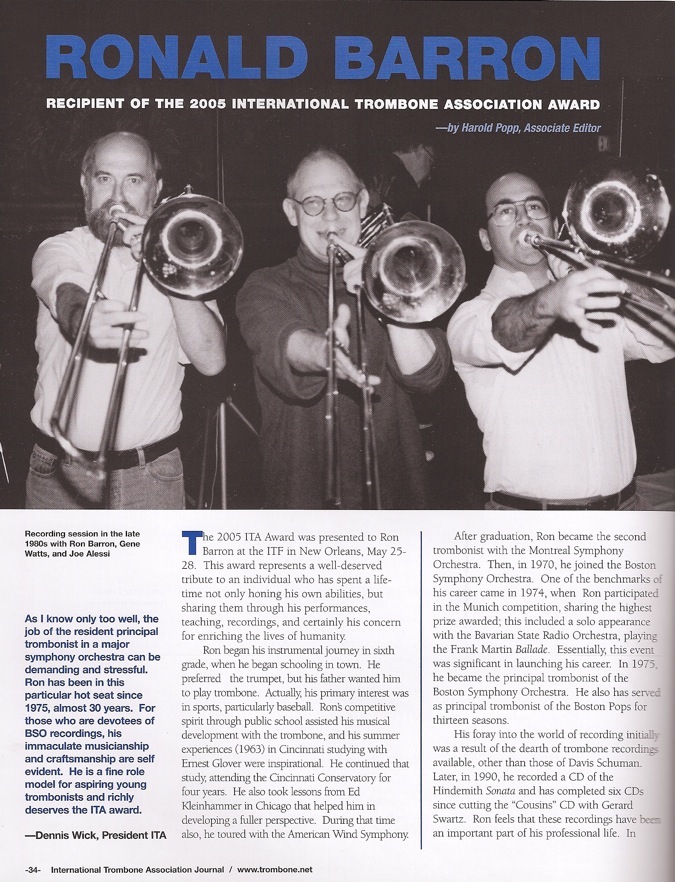

ORCHESTRAL SECTIONAL -BSO trombone section interview

By David Begnoche

At Dennis Bubert’s invitation, trombonist Dave Begnoche met with Ron Barron, Norman Bolter and Douglas Yeo, the members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s trombone section for the last twenty-two years.

DB Thank you for taking time to share your thoughts with the ITA readership. More than anything, this is really a celebration of the section as a twenty-two year era comes to an end, with two of the three of you about to retire.

RB I haven’t really thought about it like that too much, but it is a length of time, like anything. There’s a stability element within the section, and within the orchestra as well. The audition process changes and affects a lot of things. You can never tell how the change of one member can impact the entire brass section, or orchestra, for that matter.

DY And now there will be two people leaving, essentially at the same time, within the same season.

NB And you [Doug] won’t be in the new section very long.

DY No, I won’t be in the next group as long as I’ve been in this group. So this is the big part of our careers as members of the Boston Symphony. We’ve been together since May 1985.

NB The section comprises more than two-thirds of my professional career.

DY For me it will be more than two-thirds, and for Ron, almost half. We don’t have many twenty-two year periods in a lifetime. You might get three or four if you’re fortunate. We haven’t even lived three twenty-two year periods, so in many ways, this has been a defining portion of who we are.

DB Ron and Norman, you joined the orchestra a number of years before Doug, so perhaps you can talk about the evolution of the section.

RB Well, I’d been playing second [in the BSO] for five years before the principal opening happened in the late spring of ’75. When I think I first started wanting to play in an orchestra, I really didn’t aspire to play first. I think what happened was, I ended up in Montreal, and then here in Boston playing second. Being young and spirited, which I hope every young player is, circumstances led me to want to aspire to more. Then I went to the Munich competition in 1974, where I met Becquet, Slokar, Sluchin among others. By the time I came back from that I felt committed to trying to play first somewhere, but I didn’t know where it was going to be. And then Bill Gibson left Boston, so I auditioned and won the position. Norman joined soon after, bringing all his talent and drive and fire. Seiji was excited to have his first new players, and the trombones had a lot of visibility. We were kind of go-get-em young upstarts, and we played with a lot of enthusiasm. Gordon Hallberg was bowing out around the time Norman came in, and really we had many years of alternates in the bass chair before Doug joined.

NB Some things just clicked when Doug joined: there was a certain ease – that ease is really what you hope for when a new member joins. I guess that’s a big part of the audition process: it’s not just finding the best trombonist, but finding the best musician to fit your section. I think when Doug came, in many ways it was a very unifying factor. You know, Doug was very open and from the beginning Ron would say “Hey, let’s try this equipment for this piece” or “… something different for that piece.” Even back in the ’70s, we would play Bachs on the big pieces and Conns on some of the lighter repertoire.

RB That’s right. Norman and I were doing that from the first year he came into the section. On period pieces we would scale down, me on alto, Norman on a smaller bore horn, and Doug on single valve.

DB Yes, that’s one thing that seems unique to this section: your long history of using different equipment – different size, different sounding equipment – even within the same concert.

DY That’s one of the things that might be a little bit different in our section, the openness to use a wide variety of different equipment. In many sections, you’ll find all three players playing the same type of equipment. We’ve never been like that. The instruments we’ve played as our main default are simply the ones that each of us individually feels the most comfortable on. Currently, that would be Ron playing an Edwards, Norman playing a Shires, and me playing a Yamaha.

RB We really feel strongly about that, about using instruments that fit into the string and wind texture. We were devoted enough to find the color that seemed appropriate, even if it meant trying different equipment. Why not? Trumpet players do it all the time. Your concept doesn’t necessarily change, but equipment does change your overall sound, there’s no doubt about it. You know, though we’ve been using instruments by different makers lately, blend is a curious thing, and it’s not unlike like paint: if you’re trying to make a chocolate color, you have to start with white and red and blue and you mix it together and you get one unified, blended color - it doesn’t have to be three shades of brown. Maybe that’s the key to section playing. Homogeneity happens from the musicianship; the instruments are just vehicles to that end. They amplify certain possibilities. You need to play with the ear, not the lip or the eye. That’s what makes the difference. The embouchure fine-tunes what the ear really wants to make happen.

DY Just as recently as last summer, the Symphony purchased a set of five trombones by Kruspe made in the ’20s - an alto, three tenors and a bass.

NB Doug heard they were for sale, and was able to persuade the BSO to buy them to match the Austro-German rotary trumpets, like the Schagerl rotaries the trumpet section currently uses. They sound fantastic.

RB They’re really great: very colorful. It’s a quite a unique sound.

NB We did a rehearsal of Rhenish five minutes after the instruments arrived. Ron sounded phenomenal on the alto.

RB They’re perfect for that repertoire - they have such an integral woodwind-string component in a way that fits in more than the American brass instruments.

DY All that to say, we’re not into the one-size-fits-all for each other or for any piece.

NB We’ll look at each other, talk about it, and decide what we want to use. Not using it just for its own sake, but for the timbre we want, the conductor we know, the space we’re in, or other events happening in our lives.

DB Speaking of spaces where you perform, obviously Symphony Hall here is an extraordinary space. In a previous conversation, Norman, I remember you describing the hall as an extension of your instrument.

NB Very much so. I think a hall has a lot to do with the sound you create to fill the space. You can actually play with the hall and I know a lot of halls are less resonant, so sections have to do things to achieve excitement and resonance through driving perhaps more than they would want to in order to achieve their musical goal. It should always be about the musical goal. This hall seems to take certain things. For example, we went through an era when Doug and I were playing on Monettes and Larry Issacson, who was second in the Pops in those days, played a Monette too. That was a very different and special sound but everything is a point in time. We talked about time and things coming together at a certain time. At another point in time, those instruments and those people may not work. And so, can you change in order to continue to exist? I think a lot of times, players think that they need to stick with this or that, no matter how they feel, and that can shorten a lot of careers for a number of reasons.

RB You know, we never talked about it too much, but the overall sound of the orchestra – the richness in the bass in Symphony Hall – gives a fullness to the sound no matter who’s in there. The bass sound is very intense in there, and, of course, we had Chester on tuba, with this mammoth, easy sound under us. In Symphony Hall, it can lack a little diction, so you might be able to play with a little bit leaner sound and still have the hall fill it out. It makes a big difference, and day-in, day-out, it makes you hear differently - and makes you play differently if you allow it. A bad hall is not a good thing, and there are plenty of bad halls out there. We’re very lucky here. It’s the overall texture of the orchestra, and the space in which the orchestra plays. And over time, I think one becomes part of the room more than you realize. It’s not the equipment you play on. I never had in my mind that I would cultivate a particular type of sound – it’s just what seems comfortable or natural for the repertoire.

What’s fascinating to us, after all those years of Seiji saying “too loud, too loud,” now Jimmy [James Levine] is driving the strings nuts telling them to play “louder, louder.” (laughter) I’m playing louder for Jimmy than I ever did for Seiji, yet we’re never written up in the paper for overbalancing. It takes an overall orchestra.

DB Speaking of Seiji, so often people talk about the sound of an orchestra, the sound of a section and give the conductor great credit in molding that sound, sometimes rightfully so. When you look at Berlin with Karajan or Philadelphia with Ormandy, for example, there is a certain character that is unique to them. This section shares something almost unprecedented in American orchestra tenures of conductors with Seiji Ozawa, who was here the vast majority your time with the BSO.

NB Seiji was here 28 years, I think he started in ’73 and I started in ’75 or something like that.

DB So he was the conductor of hire for all three of you.

NB Yes, he hired Ron for principal (but Ron was first hired by Steinberg as second in 1970), then later, me for second and Doug for bass.

DB So how do you equate his influence on the orchestra as influencing the way the section plays?

RB You know, really, Seiji never said much one way or the other, as a style thing. Norman and I talked about this [color and equipment] early on. Many of these color things, at least in the trombone section, were a result of our internal activities, not so much Seiji – he really left us alone. [Color] came through literature more than anything else.

NB When I think about it, and I think about players that Seiji has hired at certain times, I think he was very into the individual, if he liked a player and what they had to offer. A strong musical personality, that’s what he picked. In my case I think he went out on a limb a little bit. (laughter)

DB …as he has with a few other players, Jacques Zoon [former Principal Flute] is a very unique player.

NB Charlie Schlueter [former Principal Trumpet]…

DY Jamie Sommerville [Principal Horn]…

NB Exactly: different kinds of players. Seiji picked up on something that he liked which could vary with each player depending on that “thing.” I think our section is really a microcosm of that individuality.

RB Of course, we’re mostly talking solo positions, but in general, I think that’s right. You know, I think you really need someone with a sort of extroverted confidence – put the spotlight in their face and see if they can do it – for these principal positions. And that’s what’s awkward about the trombone as an instrument: the trombone doesn’t get that many chances. I felt that my solo interests helped sustain me enough over the years that when the spotlight did come at me, I wasn’t unprepared for it. I think that’s tough for trombone players, because the function in the ensemble just isn’t that soloistic. We provide the color and the accents more than the tune; we’re the add-ons to the texture, and once in a while we get a tune, but it’s not like we’re melody instruments in the orchestra.

DB One thing that’s always stood out to me is that this section has three very strong and very vibrant personalities. We can see that individuality far beyond your instrument choices. It seems that the Symphony is just one facet in each of your musical lives, as can be seen with multiple solo recordings for each of you, as well as other interests.

NB I don’t know of any section with even one solo CD by every member.

DY Ron has nine solo trombone albums going back to Cousins and Le Trombone Français, I have five solo albums (four on trombone and one on serpent) and five with New England Brass Band as conductor and soloist, and Norman has four. The thing is, all of our albums are different kinds of things. Ron’s recording an album of alto trombone music, I’m recording with brass band, and Norman’s recording his own compositions. We have often played on each others’ albums, but largely our interests have been quite varied.

NB Each of us has found areas of interest as musicians outside the BSO that have kept us inspired and engaged as creative beings. We’ve all made choices to expand the nature of our art and integrate it into the whole of our lives. I think our section has had many influences that have helped shape us as a “section.”

DY We each have been active in different writing undertakings, too. I had one of the very first trombone websites on the internet (February 1996), even before Online Trombone Journal or ITA. Ron and Norman, too, have their own websites that are fantastic and these have given us a place to further express ourselves and share our interests with others. Then you look at the articles and arrangements…I think what Norman said is true: if you look at all the creative output, almost all self- produced, it has been something we’ve done because we love it. Norman didn’t publish a piece of his until relatively recently; he’s been composing since he was very young, but it wasn’t until mid 1990s when it blossomed into what it is today. It wasn’t like this was happening right away when Norman was twenty, first joining the orchestra, then - boom - all of a sudden he’s making solo CDs: this came later. I didn’t make my first CD until I was forty-one years old.

DY We’ve had a lot of ways of expressing our musical and life ideas. There’s been cross-pollination between the three of us and there have been a lot of individual tracks taken. I think we have all gained and learned from what the others have done.

DB It also seems that because you have been part of each others’ projects and undertakings, not just observers, this has given you each a greater understanding of each other. There is a bond when you understand a certain wavelength beyond something that you might otherwise only experience on stage together. You mentioned being part of a greater musical community, and not just unique to a row in a box known as Symphony Hall.

NB Right. I agree with that, and plus at the same time we are so individual. I know Ron is the first born, Doug the first born, I’m the first born …

DB So three alpha dogs… (laughter)

NB Yeah, three leaders in their own way, unified by musical goals. I think we’ve done pretty well considering that.

DY I think what we are saying here is something really important and I don’t think something I can stress enough: our life as three members of the Boston Symphony, that’s not our whole life. We have vibrant musical lives outside Symphony Hall and also really vibrant parts of our lives that have nothing to do with music at all. Ron owns a Bed and Breakfast and he’s a food and wine expert. My wife and I go hiking in the wildlife parks of the west and are very involved in our church. Norman’s work with Frequency Band encompasses much more than musical exploration. It’s not just “the trombone is my life.” I keep going back to [John] Swallow’s words: “trombone is something I do, it’s not who I am.” It’s a part of my identity, it becomes a vehicle to speak through so that we can express certain kinds of things, but it’s not who I am.

NB After all, a trombone career is relatively short, really. I don’t have the body I had at twenty and I don’t know how I did what I did back then. (laughs) We must be open to evolve. This is why I think it’s very important to have other interests. You know, it’s interesting because one of my principal teachers was Steven Zelmer from the Minnesota Orchestra and ironically Doug Wright, a former student of mine, took his place. He [Zelmer] was very diversified: an avid gardener, huge wine collector, stamp collector, flag collector - it was unbelievable. He would have dinners and make sure we had the right wine the right cigar and the right flag was outside. The thing is - he brought all that to his love of the orchestra. Let’s face it: where do you get the food for your art? What is it a medium for? If there aren’t other things going on, what’s your art going to express?

DB You have to have something to say if you’re going to convey anything valuable.

NB Exactly!

RB One’s life experiences, and how they enrich us and change us or make us who we are at any given time can’t help but be reflected in the way we then deal with music as a medium of expression for who we are. And if it doesn’t express who we are, or what we’re attempting to convey from the written page, then I don’t think it’s of any use - just filling up space and time, without saying anything.

DY That is a difficult thing to covey to those students at this time who are looking for the formula, the quick fix or method on how to become “great.” I say: “when was the last time you went to the Museum of Fine Arts, or when was the last time you walked through public gardens, or walked down the street and looked up instead of down?” The diversity of our experiences - the positive ones and the struggles, the disappointments and heartaches - you have to put that into your playing. When I work with a student on the Mahler 3 solo, I want to hear some of that struggle, some of their pain. I think because the trombone alone has not been the only thing in our lives we have tried to make the individuality of our voices come through, even in a section context.

NB I agree. I know we all teach and have our own styles and approaches but one thing I know we don’t do is say “it has to be like this or that.” You tailor it to the person, of course, but this cookie-cutter thing for me is “death to art” - to think this piece has to be played this way. Yes, there are informed performance practices with any given piece, but for a student to relinquish the “artistic self” to purely copy a dogmatic approach is dangerous. Hey, I don’t know exactly what Beethoven thought. I just don’t know - but I make the best assessment I can. I’m sure, though, if he thought a player was coming from the love of his piece and the genuineness of that love and that was coming through in their playing he would say “thank you,” right? Then he’d say, “now just do it a little softer.” (laughter)

DB Speaking of balancing, you alluded earlier to keys to section playing. Do you have some thoughts to share on that topic?

RB There’s an instinct that’s built after twenty-two years together that is hard to describe. When you work together, after a while you cultivate a radar. It takes listening, working together, and time.

DY Sitting next to each other all these years, I know how Norman breathes, he knows how I breathe, we know how Ron brings things in, we know what little rituals we go through before we play, we know which thing is a little more challenging for each of us, we know when we can lean on each other, we know when it’s OK to say “how ya’ doin’ ” - and when it’s a good idea not to say something….

RB Really, it’s about one word: respect. Respect for the music, respect for your colleagues (the colleagues in front of you as well as the ones next to you), and serving the music. Knowing your role is an aspect of section playing we often take for granted. You don’t really have a group, just a collection of individuals, without shared respect. Historically, the BSO directors have hired some really outstanding players, real “personalities” on their instruments, but the artistic goals are never compromised by their personal expression. It should feed into the collective, and I think it has. Leadership comes in many forms.

DY For me, and I think Ron and Norman would agree, I was very fortunate to be in this orchestra when you had some really great individual character players many of whom aren’t playing with us anymore, players like Norman’s uncle Sherman Walt [bassoon], Buddy Wright [clarinet], Vic Firth [timpani], Chester Schmitz [tuba]. These guys were individual personality players beyond compare.

NB It’s so true. Everything they played meant something. There was never a dull note. I don’t care if it was a tutti passage or not, it still had something that was alive in that passage. Blend never meant bland to them, which I think can happen all too easily. A lot of that I think is what has made the BSO unique, those kinds of players.

DY People ask me “who were your teachers” and I say, “well, I studied with Edward Kleinhammer and Keith Brown and Chester Schmitz and Vic Firth and Joe Silverstein,” and the list goes on and on. Just sitting between players like Norman and Chester for all these years has been a lesson. If you have the ears to hear, you will learn and if you are closed off like you know everything, you will never grow.

NB You know, openness and staying inquisitive is a choice. I think I’ve learned staccato from every instrument of the orchestra - how to do it like a bassoon, how to do a pizz like a cello, how to be like a muted trumpet… it’s a spectrum thing. If you don’t start to think in a different spectrum and learn from all the instruments, then you can find yourself stuck. If you asked trombonists around the world, they wouldn’t agree on things, so you have to take it in and make your own art. It’s interesting: we’re influenced by everyone we are with. Just look at the section: next to our families, we’ve probably spent more time with each other than sometimes a lot of family. I think we figured out that it’s been something like 20,000 hours together minimum; that’s a lot of time.

DY People say days move slowly and years move quickly and I can’t fathom that twenty-two years have passed.

DB As you look back on this era about to finish, what are some of your most memorable performances?

NB The Brahms Symphonies with Bernard Haitink were pretty magical and a there was Liszt Faust Symphony with Leonard Bernstein conducting that’s memorable.

RB We did the Dvořák Cello Concerto with Rostropovich years ago, which is something I’ll never forget, and some of the Miraculous Mandarin performances with Seiji stand out, too.

DY The Bruckner 3 with Kurt Sanderling was incredible. It was maybe the most beautiful and majestic Bruckner experience I have ever been in. A lot of what’s great about moments can’t be said. It’s like taking a photo of the Grand Canyon: it just doesn’t come close to giving you the real picture.

DB What about recordings?

NB The Mahler 7 would stand out to me as a special experience.

DY Some of the Spielberg stuff with John Williams. There was a scherzo for motorcycle and orchestra which we were practically sight reading on the recording. It came off a fax machine that morning and we only had time run it before recording. That was exciting!

RB You know we used to do a lot of recording. When I came into the orchestra in the ’70s, we were recording constantly. It felt like every free day was filled with recording sessions. My first Pops season, we worked six-day weeks – rehearsals in the morning, preparation for TV shows, recordings in the afternoon, concerts at night, twelve or thirteen recordings for TV shows throughout the eight weeks – all that work is gone. Today, so many kids buy this tune or that tune in a download, so we need to embrace new mediums. Those new mediums don’t provide the same visceral relationship between humans – it’s not the same thing. It’s complicated. I feel like I’m getting out of the orchestra at a time when it’s facing more challenges than when I came in. Boston is fortunate because of the structure we have with Symphony, Pops, and Tanglewood, which helps make it financially stable.

DB What advice do you have for those entering a world that two of you are leaving?

NB I still warm up and I’m 52. (laughter) In a way, it’s the same world, and in another, it’s very different. I look out over the orchestra and it’s not the same orchestra as when I joined. How could it be, thirty-two years later? There are over eighty different members. I would have to say if they are walking into an orchestra position, don’t think it’s going to be the be-all and end-all and the only thing in life. Take the other richness of your life and try to put into the orchestra because it will make that experience more meaningful and put it into perspective. It will also bring more depth to your music-making. Above all, never think there is only one way to play, because then you will be eating your own words when you have to change mouthpieces as your physiology changes, or [change] technical style when your breathing changes with age.

RB Embrace all of life and bring that into your trombone playing. Be flexible; gain your experience and your insight and your abilities as broadly as you can: you never know which ones are going to flower or provide opportunity. Increasingly, I think, people have to take risks, and really be your own advocate. I mean, just look at your quartet CD, it’s a perfect example. You have to do all that kind of stuff today, because you never know what will come out of investing in something you believe in, putting yourself out there. This career takes courage as well as skill. You know, I always looked at the term “talent” as “desire”: there has to be an aptitude at some level, but that won’t get you very far. You have to have the wherewithal and desire to stay on target, whether it’s that or anything else. I think on some level, the things that you do are a reflection of who you are.

Norman Bolter retired in December 2007, and Ron Barron will retire at the end of Tanglewood 2008.

To contact members of this section, please see their websites:

Ron Barron: www.trombonebarron.com

Norman Bolter: www.air-ev.com

Douglas Yeo:www.yeodoug.com

About the interviewer:

Trombonist Dave Begnoche maintains an active career as a freelance musician and has held positions and recorded with the Joffrey Ballet Orchestra (Chicago), Albany Symphony (NY), and the Spoleto Festival Orchestra (Italy), among others. He has performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and has recorded with the Boston Pops under John Williams. A passionate performer of contemporary music and an active teacher and clinician, Dave’s work with Pulitzer Prize winner John La Montaine has resulted in the final version of the composer’s Trombone Quartet (2006). Dave is a founding member of trombone quartet Stentorian Consort whose debut CD Myths and Legends was released on Albany Records in August, 2007.

The Mystic (CT) native was recently appointed International Trombone Association Affiliates Manager and AIM Membership Coordinator. Dave has written articles and conducted interviews for the ITA Journal, the Brass Herald and the American Composers Forum. He may be contacted at oneisdown@yahoo.com.

INSIDE THE BOSTON BRASS

An Interview with Ronald Barron by Anne Mischakoff

June 1997 Volume 51, Number 11, Page 18 The Instrumentalist Magazine

200 Northfield Road, Northfield, IL 60093

For more information, contact The Instrumentalist Magazine